The Oncology Drug Marketplace: Trends in Discounting and Site of Care

In 2015, Berkeley Research Group professionals published a white paper studying the impact of growth in the 340B program on the oncology marketplace.1 Our research found that 340B hospitals were playing an increasingly large role in oncology despite being a higher-cost site of care. Since then, the 340B program has grown an additional 67 percent, and the shift in site of oncology care to the hospital outpatient setting has continued.

In preparing this current white paper, we sought to understand:

- What role do 340B hospitals play in the continued shift in site of care to the hospital outpatient setting, and what financial incentives exist for 340B hospitals to expand oncology services?

- How large are statutory discounts and rebates (e.g., 340B discounts, Medicaid rebates, federal supply schedule discounts) on oncology drugs relative to discretionary price concessions, and how have they evolved?

- What role may changes in the volume of statutory discounts and rebates have played in drug pricing decisions by pharmaceutical manufacturers?

The results of our analysis confirm what other studies have shown: 340B hospitals are playing an increasingly large role in oncology. Although the unintended consequences of policy decisions and market forces that have contributed to the rapid growth in the 340B program cannot be fully understood at this point, our research resulted in a number of important findings:

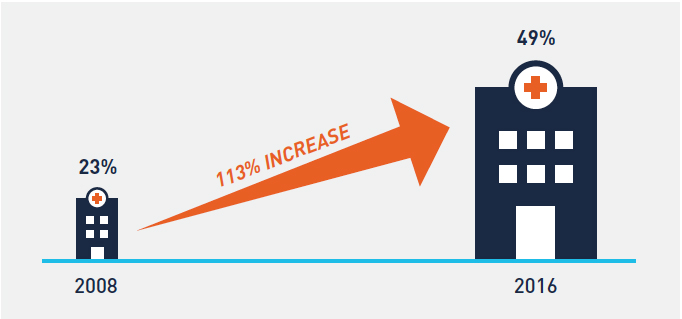

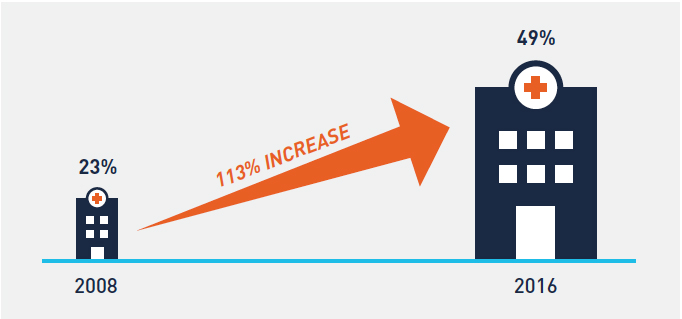

- Shift in site of oncology care from the physician office to the hospital outpatient setting has continued unabated since 2008, and almost 50 percent of 2016 Medicare Part B chemotherapy drug administration claims occurred in the hospital outpatient setting—up from just 23 percent in

- 340B hospitals, which now account for 67 percent of Medicare Part B hospital oncology drug reimbursement versus 38 percent in 2008, have played an outsized role in this shift in site of

- Average profit margins on Part B-reimbursed physician-administered oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price increased from 40 percent in 2010 to 49 percent in 2015 and have created substantial financial incentives for 340B hospitals to expand oncology services, despite overall healthcare costs increasing as a result of this shift in site of

- Growth in 340B purchases of oncology drugs and the expansion of Medicaid tripled the volume of statutory discounts and rebates on drug sales between 2010 and 2015, putting upward pricing pressure on drugs accounting for these discounts and

Background

Over 15.5 million Americans with a history of cancer are alive today.2 Research shows that as the overall cancer death rate has declined, the number of cancer survivors has increased.3 Additionally, the absolute number of new cancer diagnoses has continued to rise annually as the US population grows and ages.4 Patients are treated in a broad network of physician practices, outpatient treatment centers, dedicated cancer hospitals, and inpatient facilities across the country. However, as demonstrated in Figure 1, where patients receive their cancer care has change substantially since 2008. Due to a variety of factors, almost half of all cancer patients are now treated in hospital outpatient facilities—up from just 23 percent in 2008.

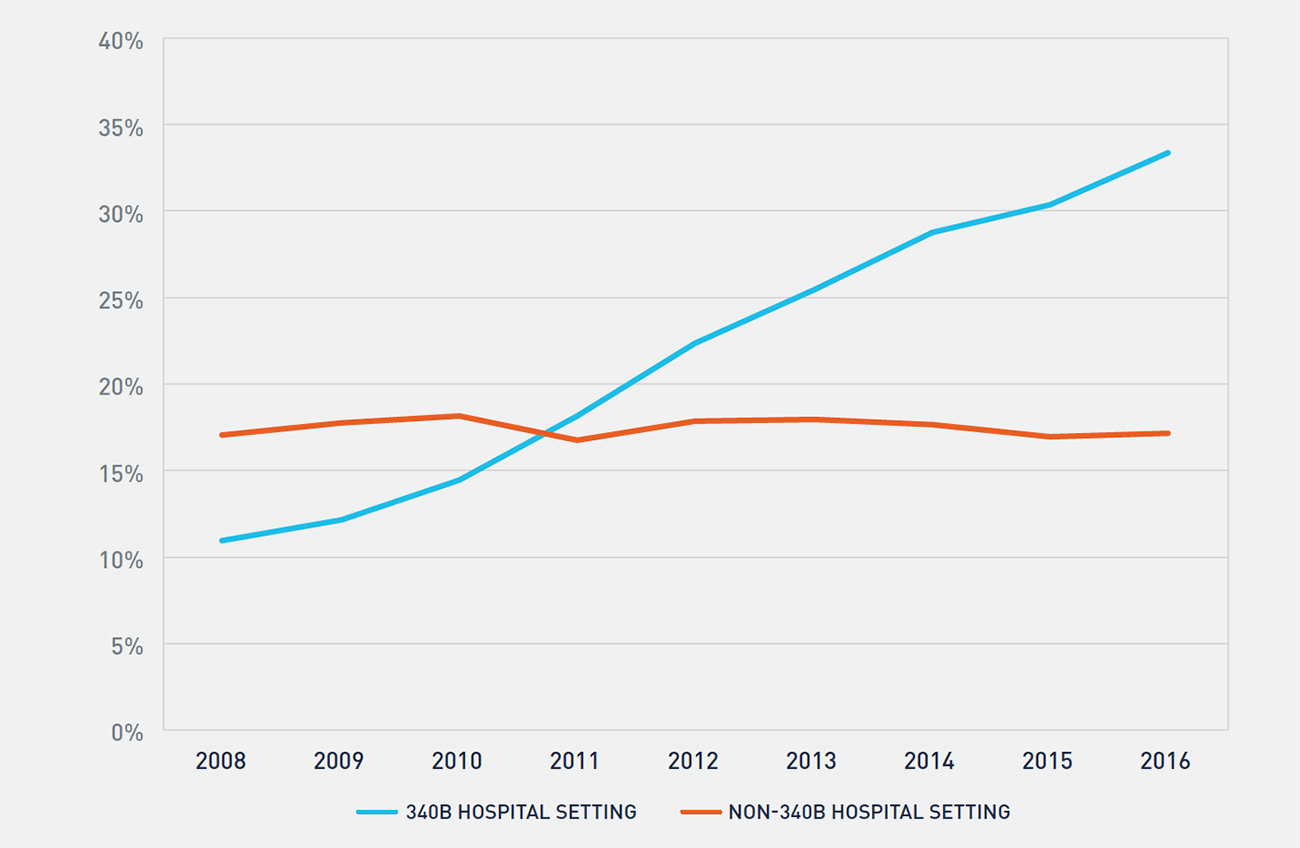

FIGURE 1: PERCENT OF TOTAL CHEMOTHERAPY DRUG ADMINISTRATION CLAIMS IN THE HOSPITAL OUTPATIENT SETTING

Although limited research exists on the impact of this shift in site of care on patient outcomes and quality of care, there is substantial evidence that overall healthcare costs increase as a direct result of the shift in site of care. In its March 2015 Report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) commented that the shift in site of care from physician offices to hospital outpatient departments increases program costs and costs for beneficiaries.5 Other studies specific to oncology have found that the cost of care for cancer patients is significantly higher in the hospital outpatient setting than in the physician office setting, despite similar resource use and clinical, demographic, and geographic variables.6

As oncology treatment costs, which now exceed $87 billion, have continued to grow over the last decade,7 the shift of oncology care to a higher-cost setting has become increasingly important to Congress and the current administration. In an effort to prevent hospitals from being overpaid for items and services under the historically more generous Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (HOPPS), Congress passed a hospital site-neutrality payment provision in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 that lowered reimbursement for certain “off-campus outpatient departments.” In November 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services finalized the HOPPS final rule that reduced payment for certain physician-administered drugs purchased at a 340B price by almost 27 percent. This reduction in reimbursement is intended to better align reimbursement with the actual acquisition cost of drugs reimbursed through HOPPS and to lower drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries.8

The continued shift of oncology care to the hospital outpatient setting, combined with increased rates of cancer and rising drug prices, is setting the stage for higher overall costs of oncology care. Although Congress and the administrations have taken action in recent years, it is unclear what effect, if any, this will have on current trends. In this study, we explore the role 340B hospitals have played in the shift in site of care and evaluate the potential impact of growth in 340B and Medicaid on drug prices.

Findings

We developed our analysis using two distinct sets of oncology drugs. For analysis of the shift in site of care and 340B utilization rates, we relied on Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) claims (2008 through 2016), which include data on reimbursement for all separately payable oncology drugs. We utilized a combination of IMS wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) sales data (2010 through 2015) and publicly available pricing data to conduct financial analysis of sales, discounts, rebates, and 340B margins on a subset of the separately payable oncology drugs that accounted for 85 percent of total Medicare Part B oncology drug reimbursement in 2015. Detailed information on data relied upon in this analysis (including for the table and figures) and our methodological approach is included in the appendix.

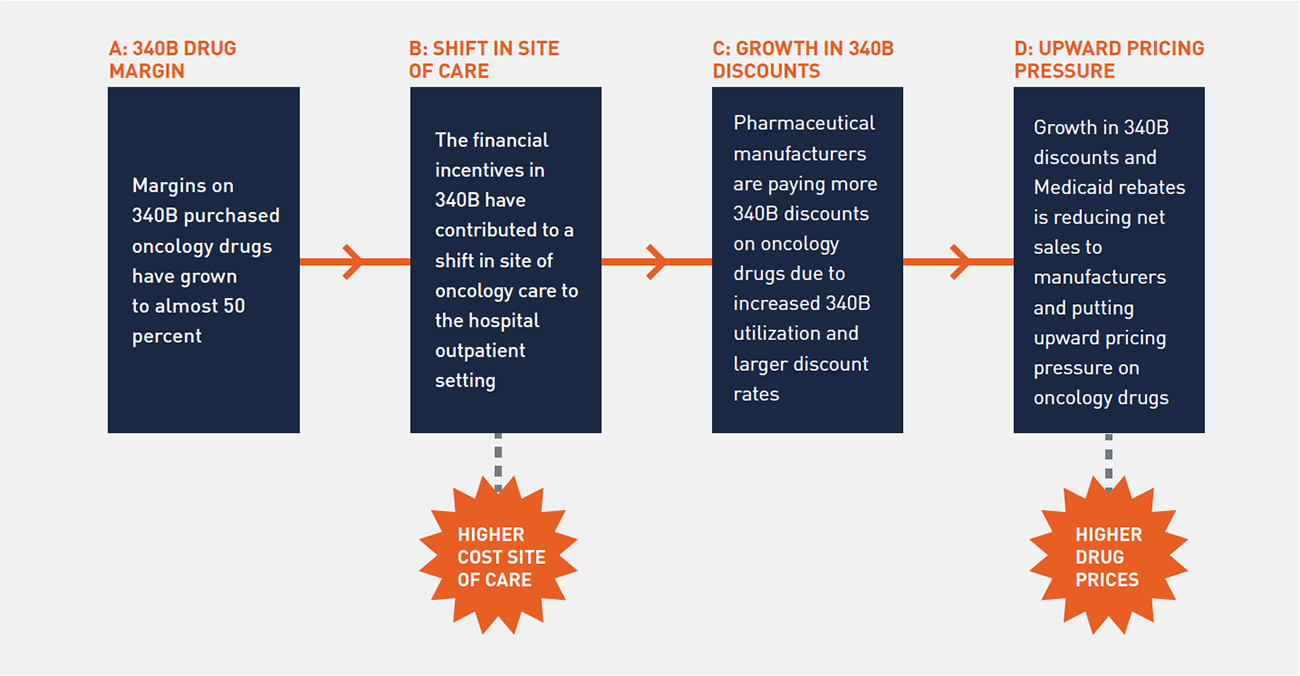

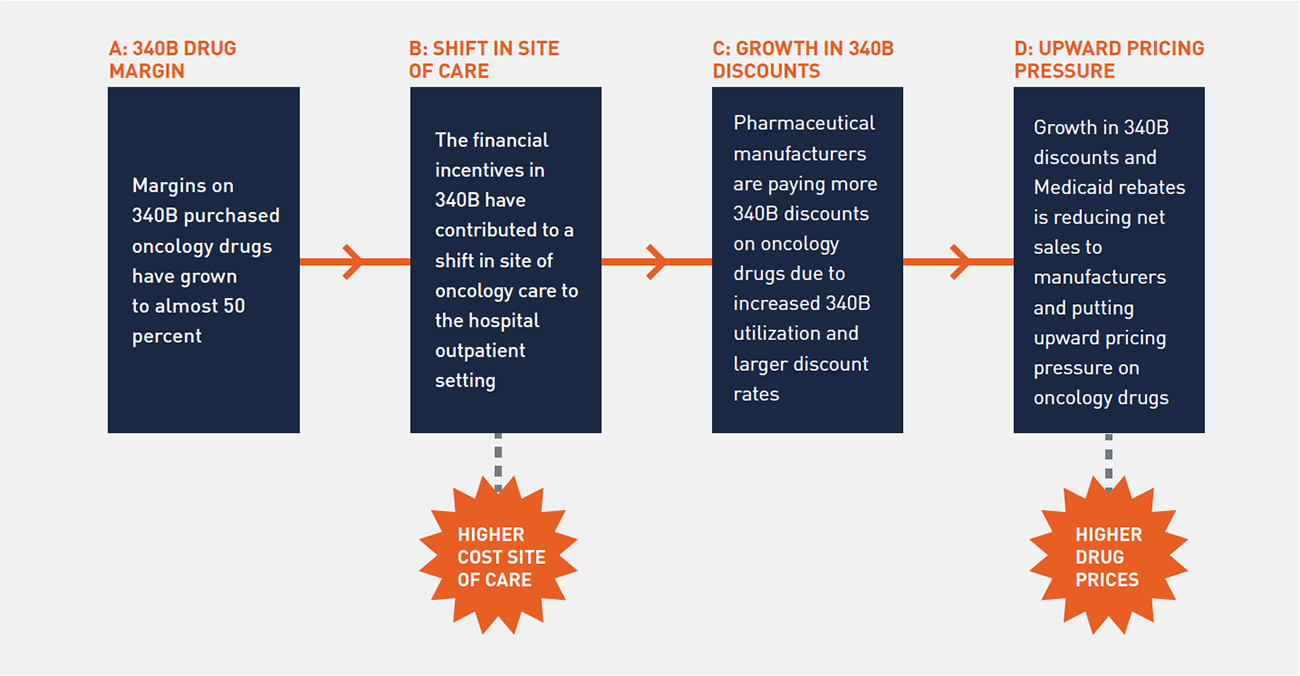

Our study considered a broad range of related topics, including the site of oncology care, role of 340B hospitals in oncology, and impact of 340B discounts and Medicaid rebates on drug pricing. A clear narrative emerged from our analysis regarding the intersection of 340B and the site of oncology care and recent trends in drug pricing. Figure 2 depicts how high-profit margins on oncology drugs purchased at 340B prices are leading to a shift in the site of oncology care, resulting in upward pricing pressure on drugs.

FIGURE 2: IMPACT OF 340B ON ONCOLOGY

1. 340B Hospitals Have a Clear Financial Incentive to Expand Oncology Services

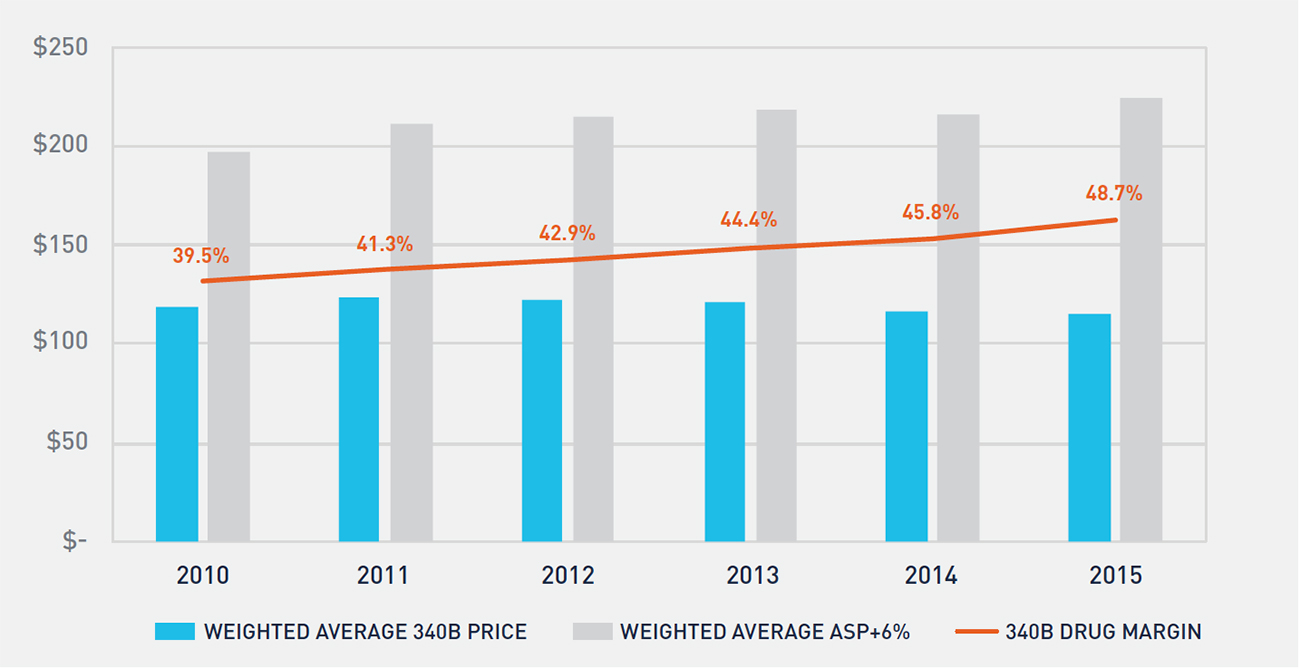

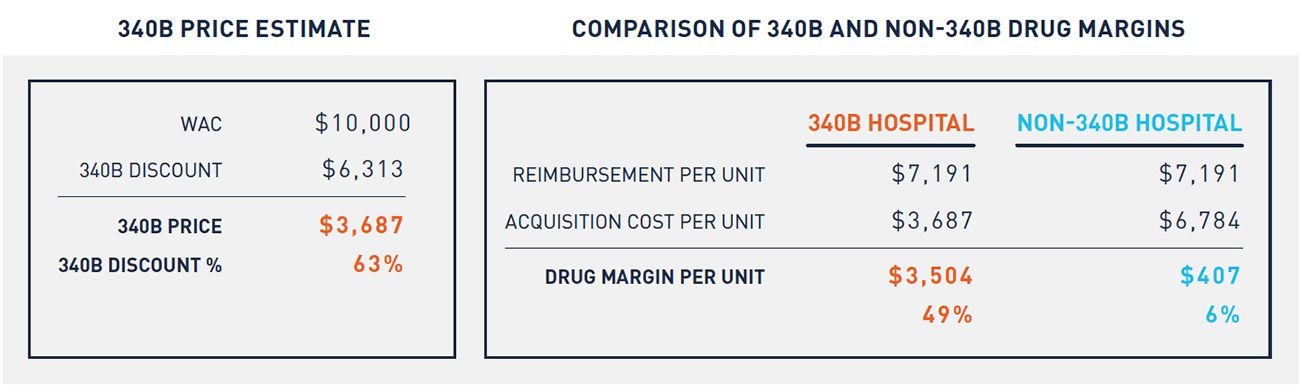

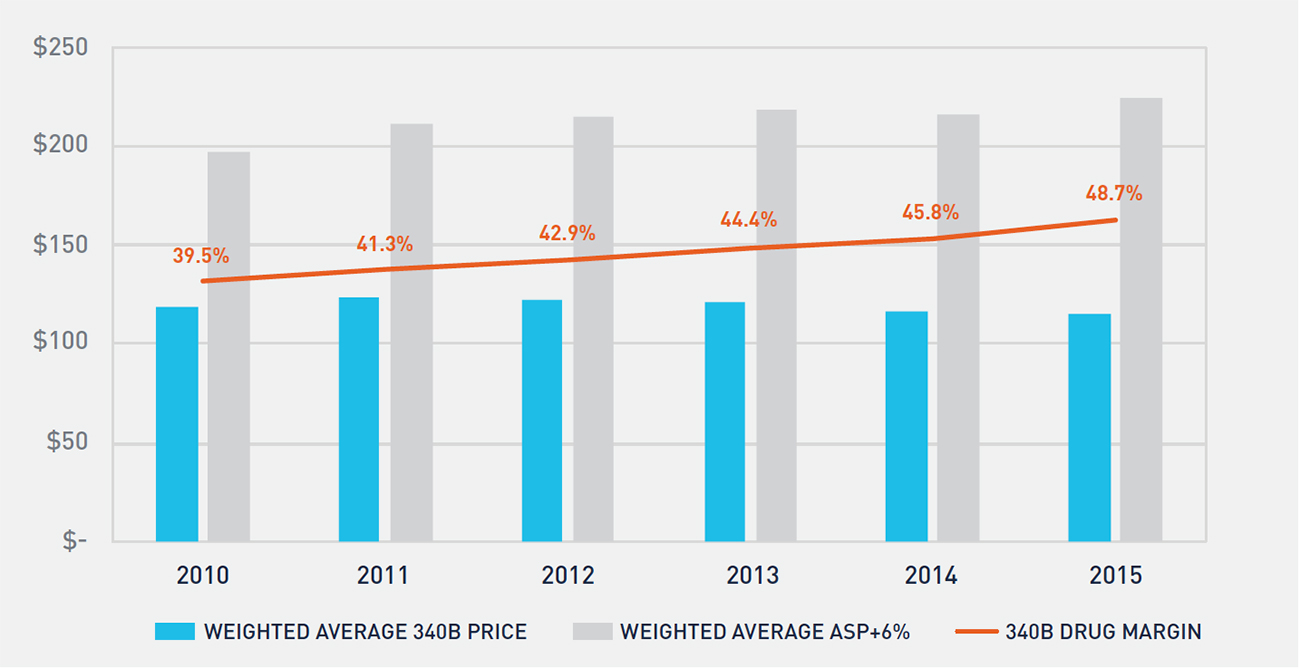

The 340B price is a statutory price derived by subtracting the Medicaid Unit Rebate Amount (URA) from the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). Because the 340B price is tied to the Medicaid URA, 340B prices track closely to the net Medicaid price. From 2011 to 2016, the average discount of a drug’s list price for Medicaid increased from 44 percent to 51 percent.9 Similarly, for the physician-administered oncology drugs included in this study, we estimate that the average 340B discount from WAC increased from 54 percent in 2010 to 63 percent in 2015, which effectively has kept the 340B price constant over this time period (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: TREND IN ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT, 340B PRICES, AND 340B PROFIT MARGIN

Medicare reimbursement for physician-administered drugs equals 106 percent of a drug’s average sales price (ASP). Figure 3 shows the historical trend in Medicare reimbursement and 340B prices for oncology drugs, as well as the profit margin realized by 340B hospitals on oncology drugs. Non-340B hospitals’ drug costs track closely to ASP, resulting in a 6 percent margin versus the 49 percent margin realized by 340B hospitals in 2015.

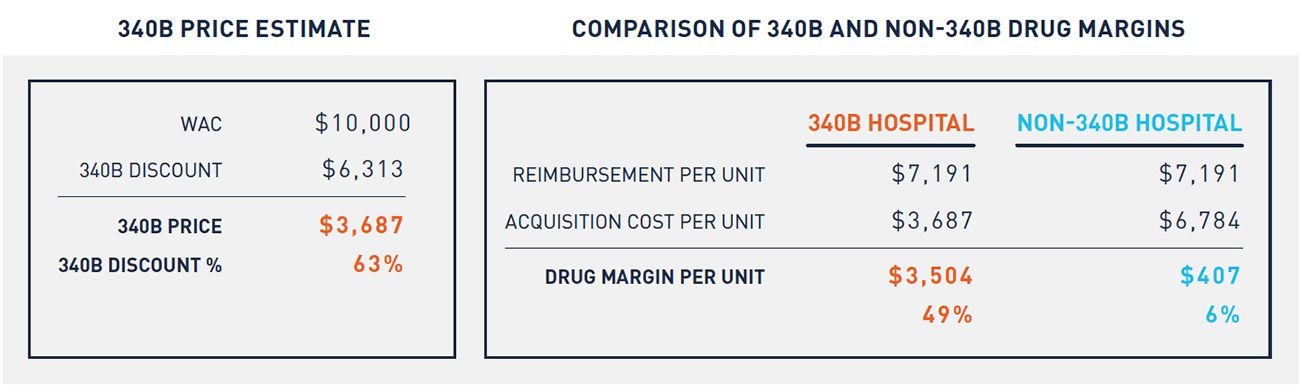

Table 1 depicts a hypothetical example of an oncology drug with a WAC of $10,000 per unit. Reimbursement for this drug is the same across 340B and non-340B hospitals. Because 340B hospitals purchase at a significantly lower price, however, they earn significantly greater profits on the same drugs than non-340B hospitals. This dynamic creates a financial incentive for 340B hospitals to administer a higher volume of oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price. This incentive has increased significantly since 2010.

2. 340B Hospitals Receive over One-Third of All Part B Oncology Drug Reimbursement

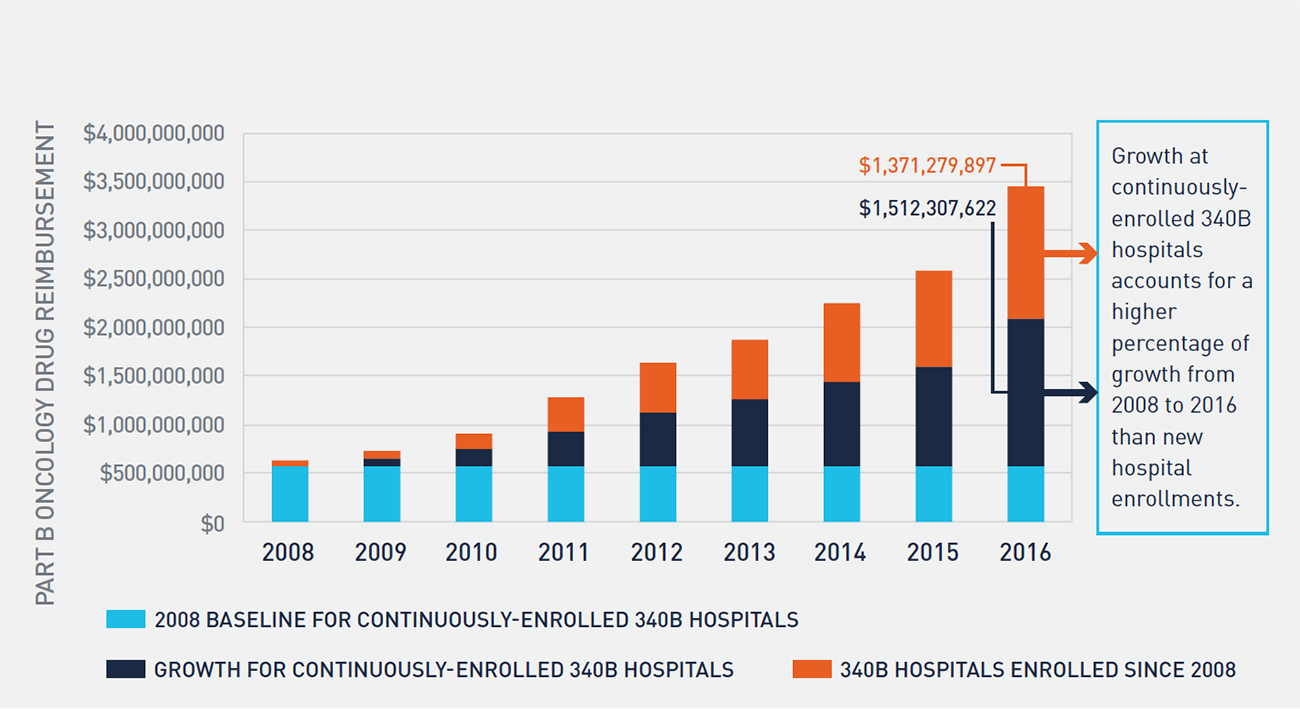

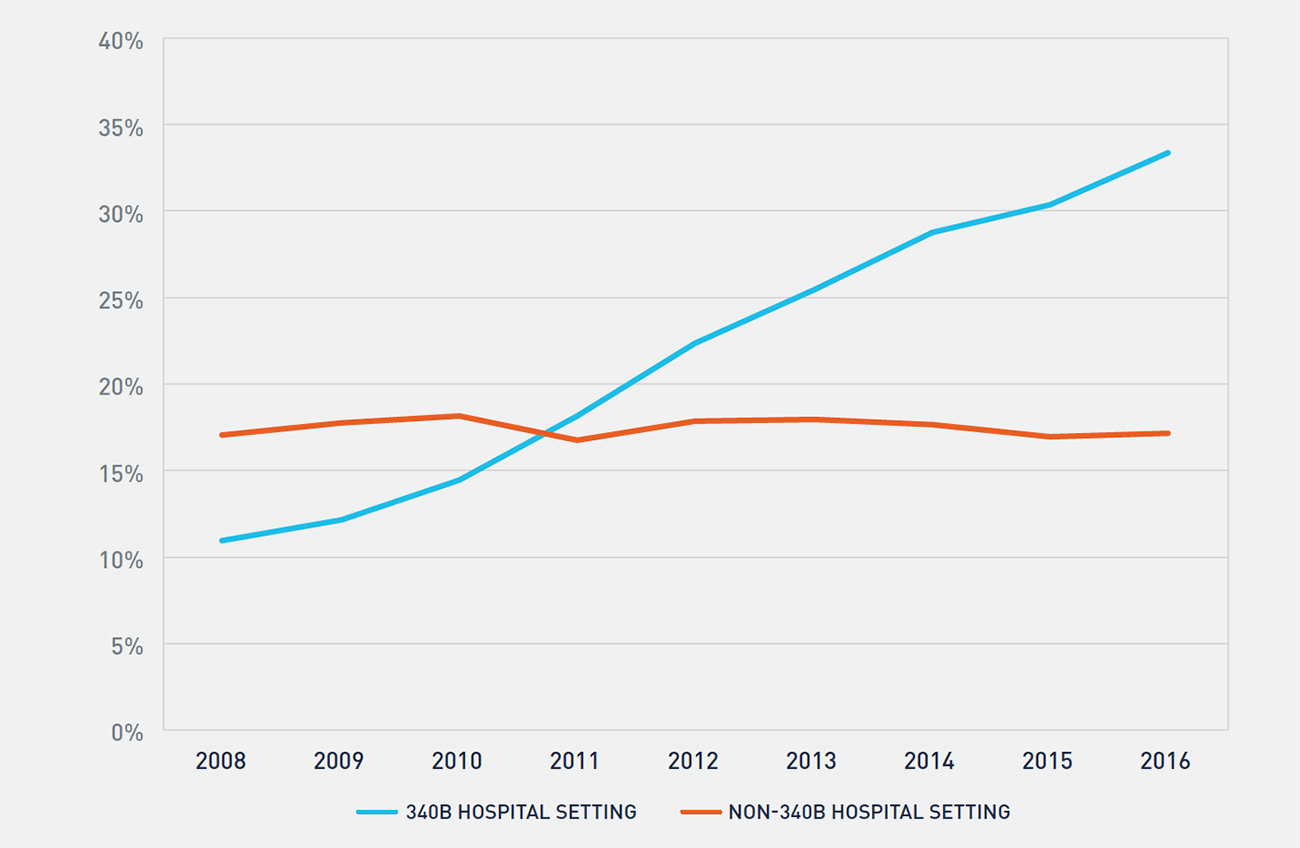

Growth in the 340B program has been well documented through various studies and data released by the Health Resources and Services Administration. Multiple factors contribute to growth in the program, including new entity enrollment, growth in contract pharmacy, and expansion of oncology services by 340B hospitals. In prior research, we explored factors that contributed to 340B hospitals’ expansion of oncology services and found that the financial incentives created through access to 340B prices is a primary driver of this expansion.10 Figure 4 shows the historical trend in oncology drug reimbursement to 340B-enrolled hospitals and the impact of expansion of oncology services at 340B hospitals.

FIGURE 4: PERCENTAGE OF PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT TO 340B AND NON-340B HOSPITALS

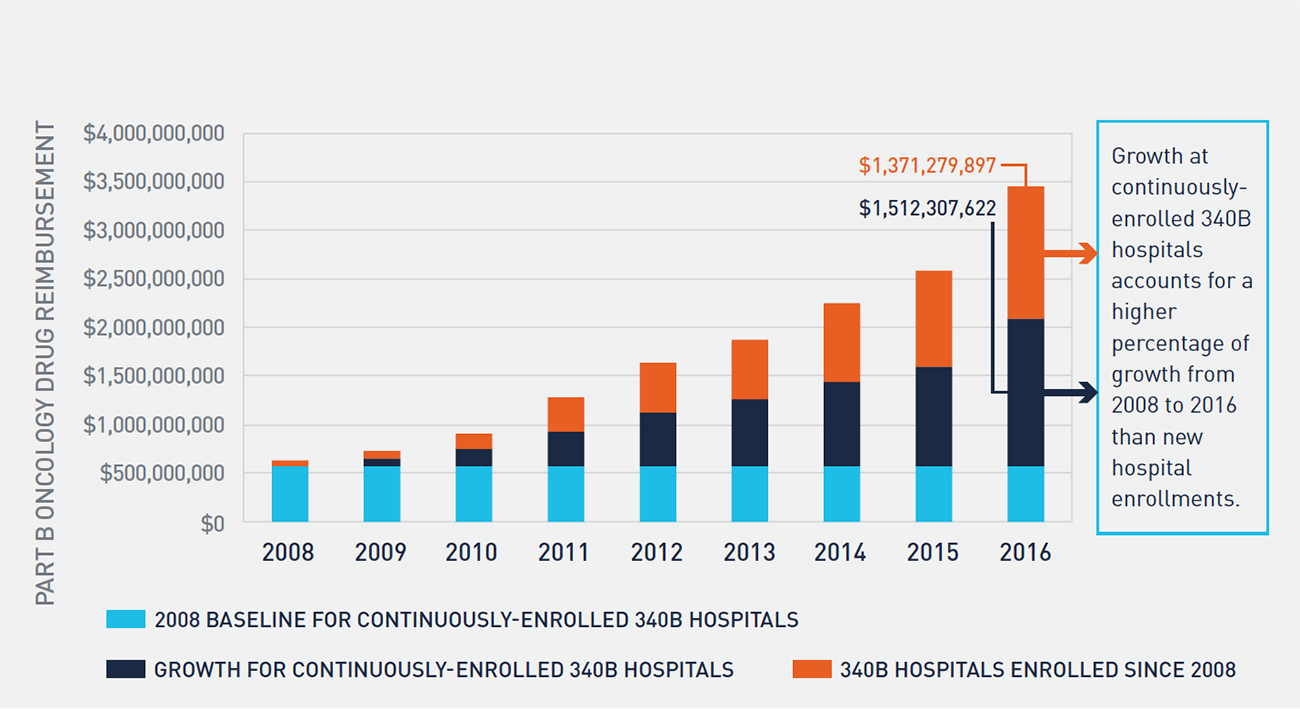

Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of oncology drug reimbursement to 340B hospitals has more than tripled, and 340B enrolled hospitals now receive over one-third of all Part B oncology drug reimbursement. During the same period, the percentage of oncology drug reimbursement to community oncology practices has declined from 72 percent to 49 percent, while non-340B hospitals’ reimbursement has remained largely unchanged. While 340B utilization rates vary across therapeutic categories and by method of administration, access to 340B pricing plays a substantial role in the site of care for physician-administered oncology drugs. Further, there is evidence that this trend will continue. Growth in 340B utilization rates of oncology drugs has historically been driven by two factors: enrollment of new 340B hospitals and expansion of oncology services at existing hospitals. Despite considerable attention having been paid to the number of new hospital enrollments in 340B over the last six years, the majority of growth in 340B utilization of oncology drugs between 2008 and 2016 actually stems from expansion of oncology services at 340B hospitals enrolled for the entire period (see Figure 5). With over 2,300 hospitals now enrolled in the 340B program, there is little evidence that this growth will slow in the coming years.

FIGURE 5: GROWTH IN PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT TO CONTINUOUSLY ENROLLED AND NEWLY ENROLLED 340B HOSPITALS

3. A Disproportionate Share of the Shift in Site of Care Is Attributable to 340B Hospitals

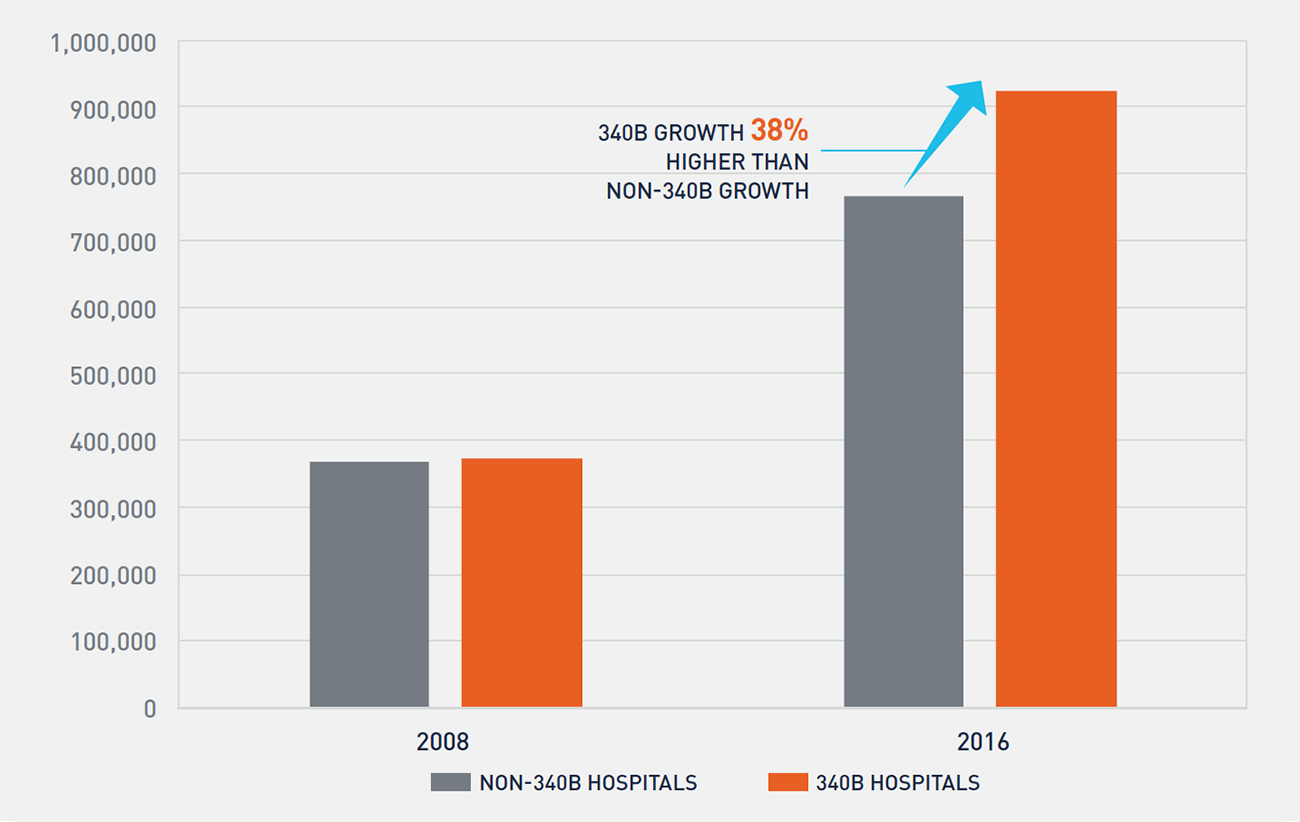

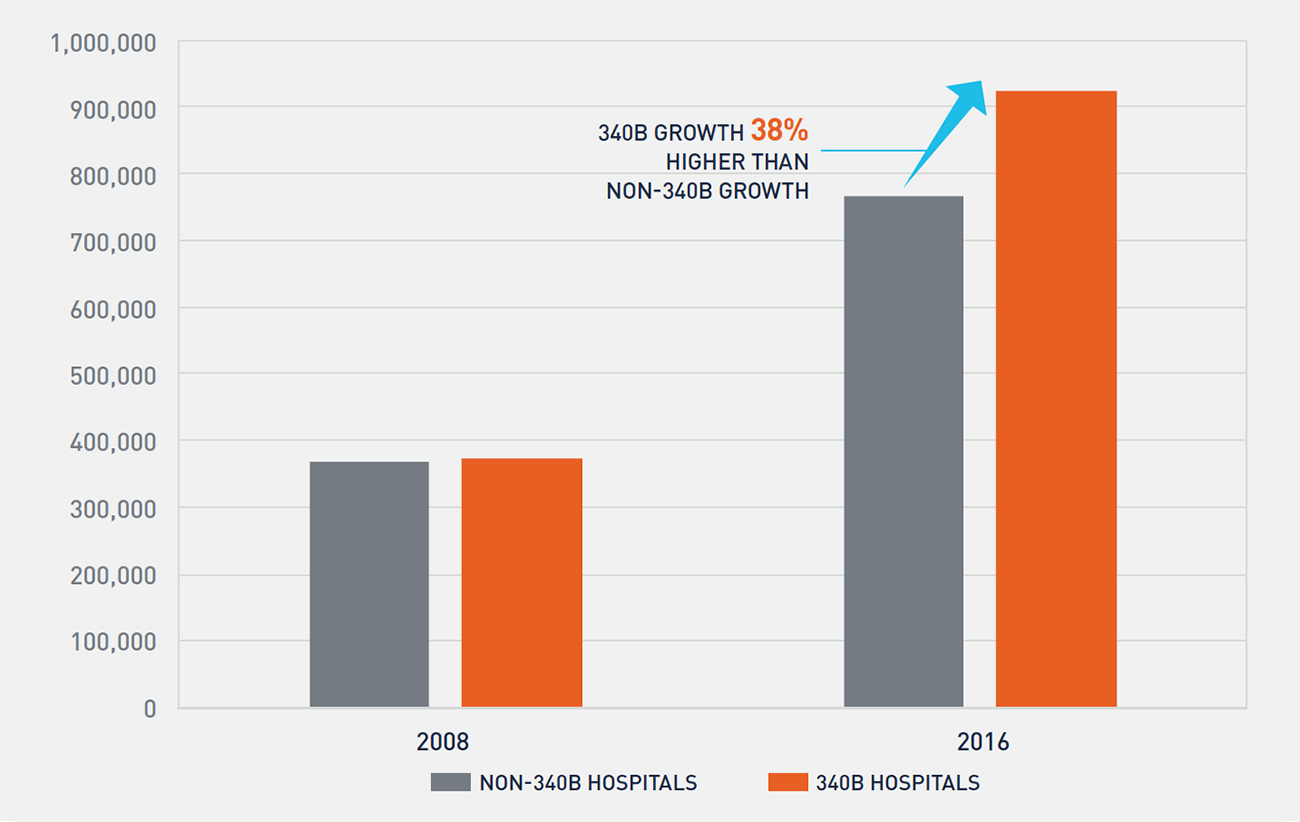

Although the percentage of Part B oncology drug reimbursement to 340B covered entities has clearly increased, multiple factors contribute to this growth, including enrollment of new hospitals. To study whether 340B hospitals are disproportionately driving the shift in site of care for oncology services, we analyzed the enrollments of two cohorts between 2008 and 2016: the first comprised hospitals that were continuously enrolled in 340B, and the second comprised hospitals that were not enrolled in the 340B program at any point. In 2008, each cohort had approximately 370,000 oncology claims (see Figure 6). However, by 2016, the 340B cohort accounted for over 920,000 oncology claims—38 percent greater growth than the non-340B cohort.

FIGURE 6: GROWTH IN PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG CLAIMS FOR 340B AND NON-340B HOSPITALS

Although both cohorts of hospitals are expanding oncology services, Figure 6 demonstrates that 340B hospitals are growing at a faster pace than non-340B hospitals as measured by oncology claims. This is potentially further compounded by findings from a June 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office, which found that in 2012 average per-beneficiary Part B drug spending at 340B hospitals was 140 percent higher than at non-340B hospitals.11 From our analysis, it is unclear whether non-340B hospitals are expanding oncology services as a competitive response to 340B hospitals’ actions or if other factors, such as the introduction of new oncology drugs and growth in the number of patients treated for cancer, are resulting in both cohorts of hospitals expanding oncology services.

4. Between 2010 and 2015, Statutory Discounts and Rebates Paid by Manufacturers Have Almost Tripled and Put Upward Pricing Pressure on Drugs

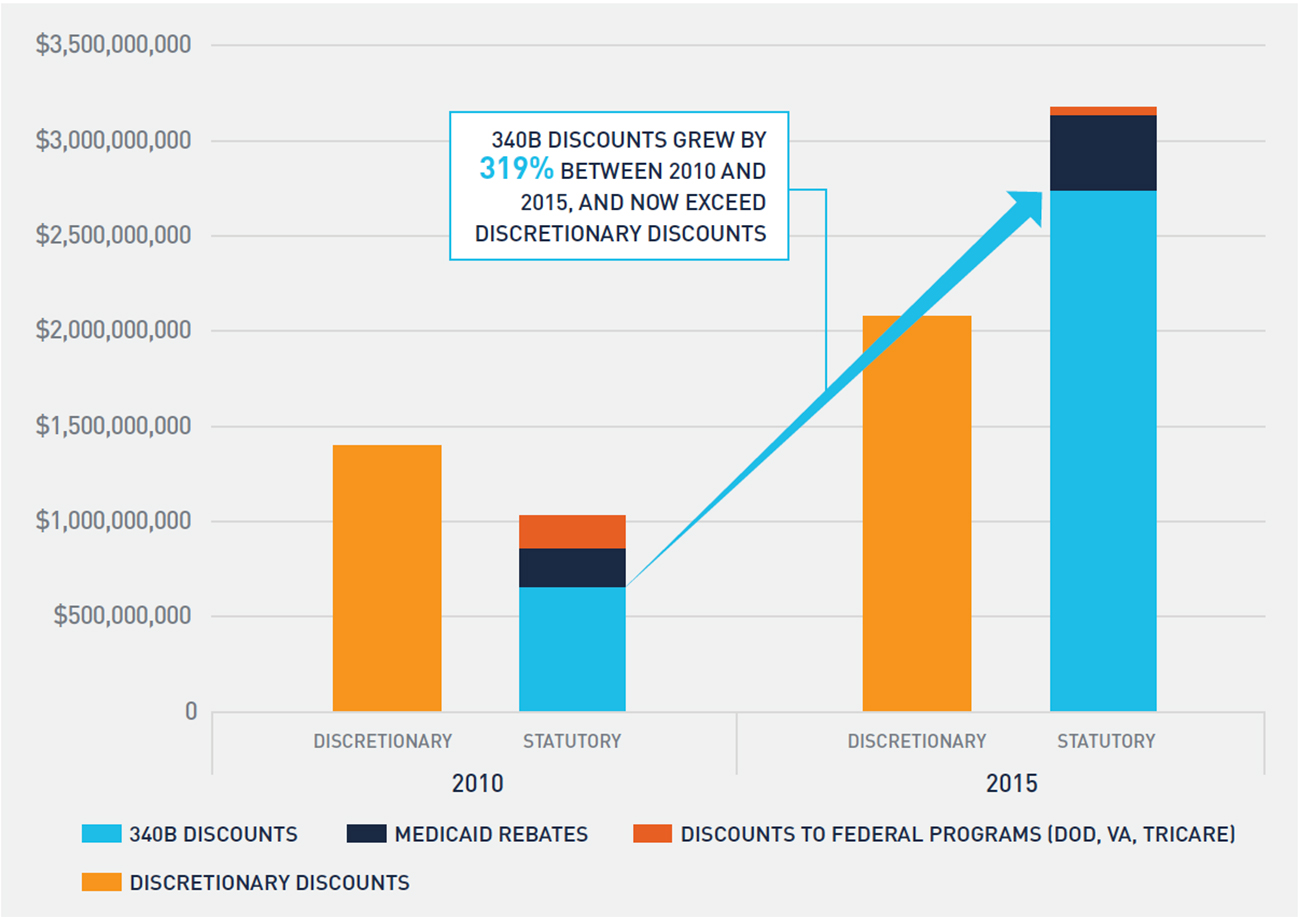

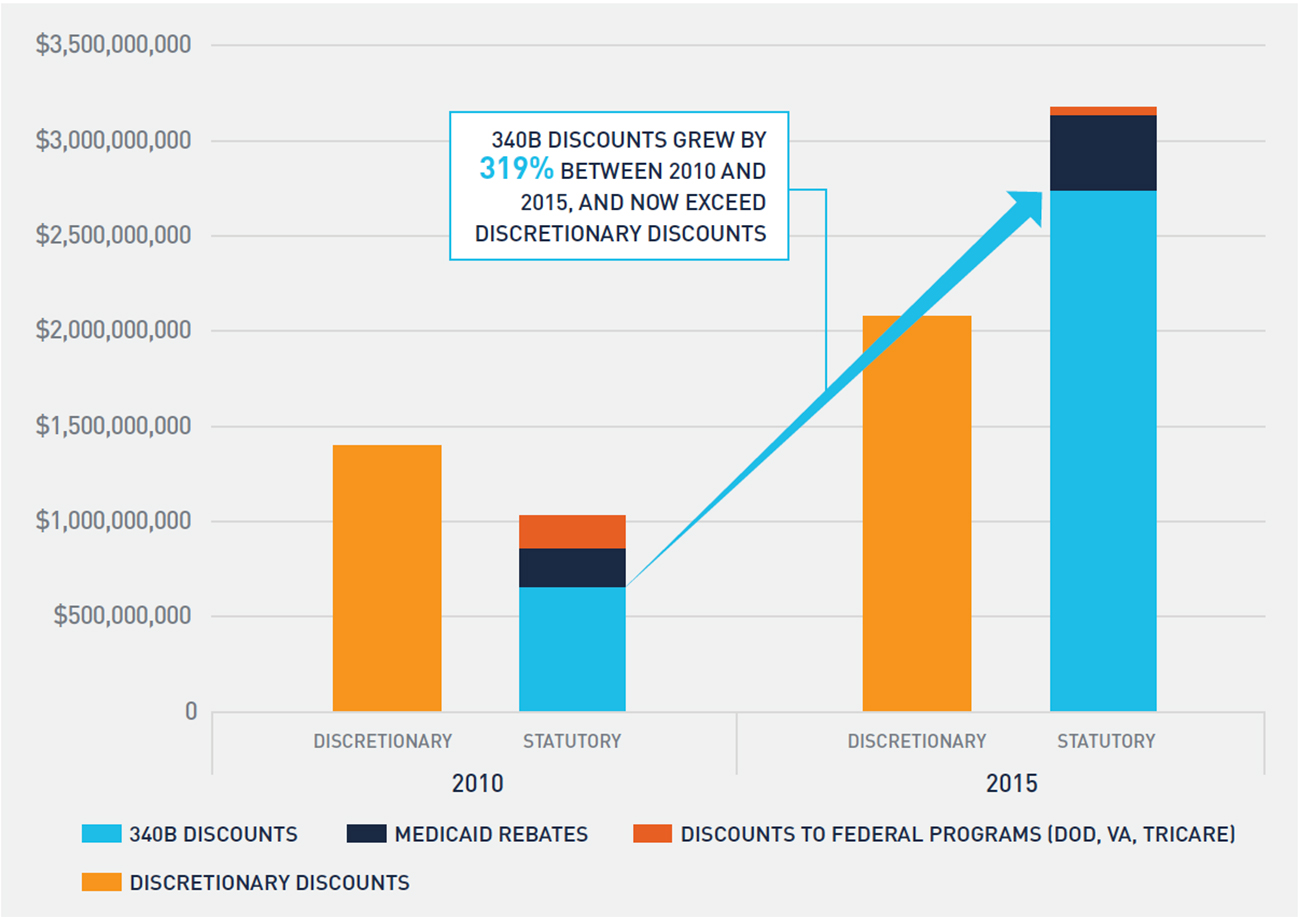

Drug manufacturers are required by law to pay statutory discounts and rebates for drugs purchased through various federal programs and agencies. These programs include 340B, Medicaid, and government agencies that purchase through the federal supply schedule. In 2010, the statutory discounts and rebates on the oncology drugs included in our financial analysis were approximately $1 billion and represented 7.4 percent of total gross sales for these drugs. By 2015, statutory discounts and rebates on the same set of drugs exceeded $3 billion and represented 14.4 percent of total gross sales for these drugs. It is evident from Figure 7 that the primary driver of the increase in statutory discounts and rebates is the 340B program. The growth in 340B discounts is a function of both a higher volume of oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price and a larger average 340B discount amount on these drugs, as noted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 7: CHANGE IN STATUTORY AND DISCRETIONARY PRICE CONCESSIONS ON ONCOLOGY DRUGS

As statutory discounts and rebates increase, net sales realized by drug manufacturers decline, which places upward price pressure on drugs. These pressures can lead to higher list prices or reductions in discretionary discounts and rebates to commercial purchasers, such as group purchasing organizations and community oncology practices, to offset growth in statutory discounts and rebates. Although the volume of discretionary discounts offered to commercial purchasers increased between 2010 and 2015, discretionary discounts as a percentage of gross sales actually declined from 10.1 percent to 9.4 percent.

Similarly, the growth in statutory discounts and rebates puts upward price pressure on new launch drugs. Consider a drug that is launched in 2010, when statutory discounts and rebates represented 7.4 percent of gross sales. A launch price of $100 would net $92.60 when accounting for statutory discounts and rebates. However, by 2015, the same drug would need a launch price of $108.10 to net the same $92.60 due to the increase in statutory discounts and rebates.

Additional upward price pressure for launch drugs exists because the 340B price can only increase at the rate of inflation. As a result, pharmaceutical manufacturers must account for the likely continued expansion of 340B utilization in the future to properly price a drug. Given recent growth trends in the 340B program, manufacturers are likely anticipating greater 340B utilization in the future and factoring it into launch prices.

Conclusion

Oncology is undergoing a dramatic shift in site of care from the physician office to hospital outpatient setting. Fueled by profits on oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price, 340B hospitals are expanding oncology services while at the same time increasing costs for patients and payers. Recent trends in 340B utilization indicate no slowdown of program growth in the near term. Reports by GAO, MedPAC, and others have highlighted this increased cost burden, and the current administration has taken action to offset some increased costs to Medicare patients.

This study also demonstrates how growth in statutory discounts and rebates—primarily 340B discounts—leads to upward price pressure on drugs. Absent additional legislative and/or regulatory action, we believe the trends identified in this study will not only continue but potentially accelerate in the coming years.

Appendix

The analyses in this report fall within two categories: shift in site of care/340B utilization analysis and financial/pricing analysis. Each category of analysis relied on a distinct subset of oncology drugs and different data sources. In addition to providing detail on which oncology drugs are included in our analysis and data relied upon, we also provide detail on our methodology and assumptions.

1. Shift in Site of Care/340B Utilization Rate1

The primary data source for this set of analytics was Medicare FFS claims data for calendar years 2008 to 2016. Specifically, the datasets analyzed were the following:

- Medicare Outpatient Research Identifiable Files (RIF) for 2008 to These data sets provide 100 percent of Medicare FFS claims submitted by institutional outpatient providers.

- Medicare Carrier Limited Data Sets (LDS) for 2008 to These data sets are also known as the Medicare 5 Percent Carrier Files or the Physician/Supplier Part B Claims Files. They contain a 5 percent sample of fee-for-service claims submitted on a CMS-1500 claim form, primarily by non-institutional providers.

These claims datasets include reimbursement amounts by Medicare and its beneficiaries, as well as HCPCS codes identifying specific drugs and chemotherapy administration procedures.

Shift in Site of Care

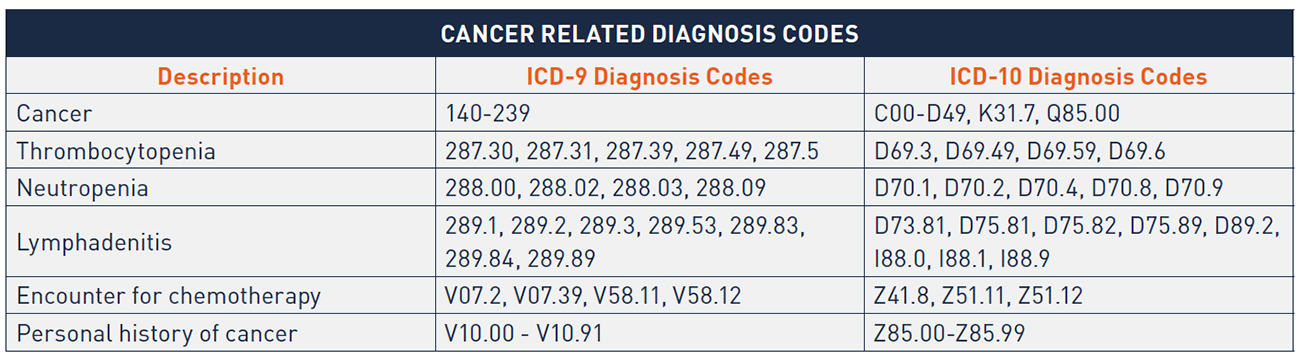

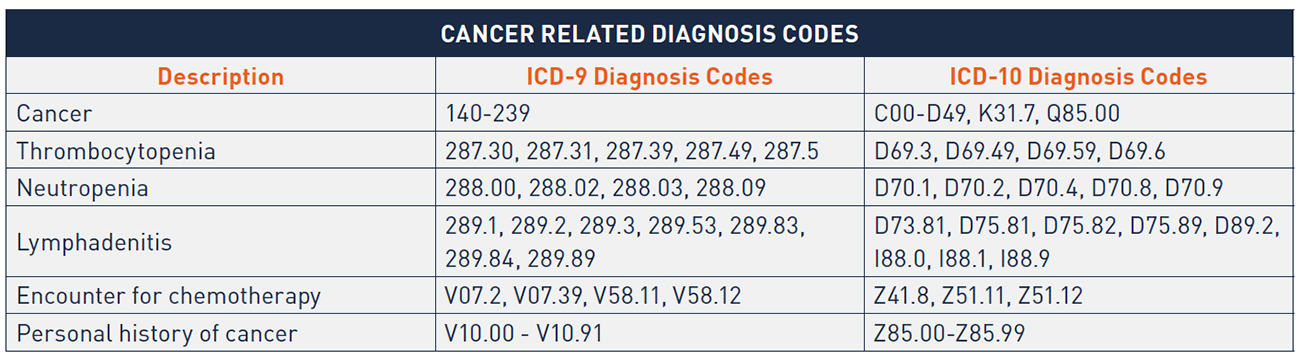

For the shift in site of care analysis summarized within Figure 1 in this report, we counted, on an annual basis, all claims within the Medicare Outpatient RIF with a bill type beginning 13 (Hospital Outpatient) or 85 (Critical Access Hospital) where a chemotherapy administration code within the CPT code range 96360 to 96549 was used and where a diagnosis code of cancer appeared on the claim. A diagnosis of cancer includes a primary or secondary ICD-9 or ICD-10 code within one of the following ranges:

We applied the same parameters (with the exception of the bill type limitation) to the Medicare Carrier LDS file and multiplied the annual count of claims by twenty to extrapolate the results yielded from the 5 percent sample of all Medicare Physician/ Supplier Part B claims.

340B Utilization Rate

For Figures 4, 5, and 6, we analyzed Medicare claims for Part B Oncology drugs. This included HCPCS codes beginning with J9, as well as a small number of other HCPCS codes beginning with J, A, or Q that are indicated for use in the treatment of cancer. We identified all claims in the Medicare Outpatient RIF file and the Medicare Carrier LDS file where one of these HCPCS codes was listed on the claim. For the Medicare Carrier LDS file, we multiplied resulting claim counts and reimbursement amounts by twenty to extrapolate the results yielded from the 5 percent sample of all Medicare Physician/Supplier Part B claims. For the Medicare Outpatient RIF file, we further limited to bill types beginning with 13 or 85. We identified claims occurring at 340B hospitals by checking that the date of service on the claim fell within a period in which the hospital was enrolled in the 340B program based on the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs Covered Entity database. Our analyses considered both payments by Medicare and beneficiary cost-sharing payments.

2. Analysis of Sales, Discounts, and 340B Margins2

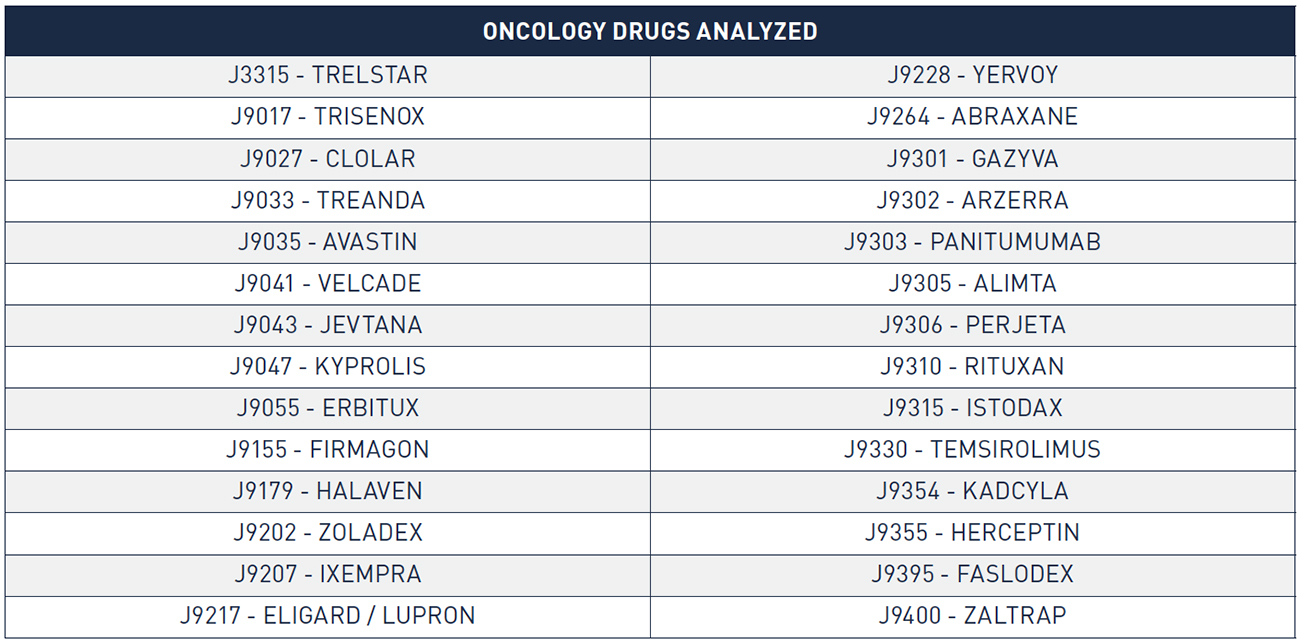

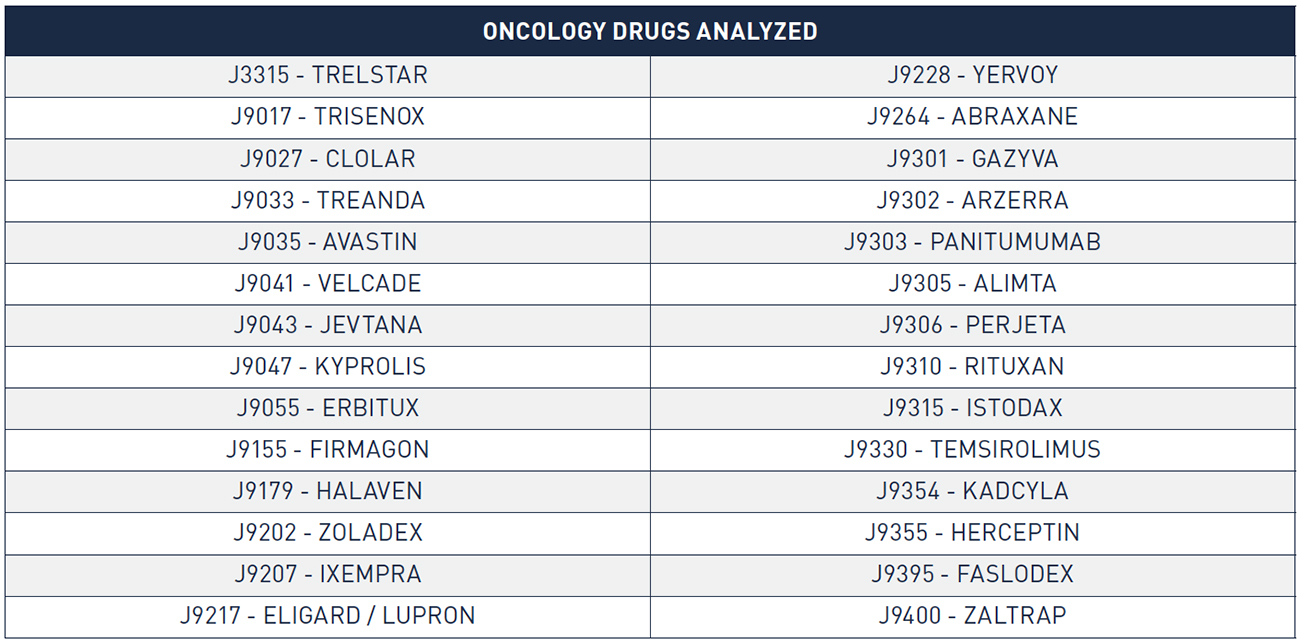

In analyzing sales, discounts, and 340B margins for oncology products, we relied on WAC sales data from IMS that was available for the period from 2010 to 2015. We used this data to analyze a set of oncology drugs corresponding to twenty-eight distinct HCPCS codes/eighty-two National Drug Codes (NDCs). We selected these twenty-eight HCPCS codes following a validation review in which we compared WAC sales to available public benchmarks (i.e., total Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement for the drug) to ensure completeness of the WAC sales data. Collectively, these HCPCS codes account for the significant majority (85 percent) of total Medicare Part B oncology drug reimbursement in 2015, the most recent year for which WAC sales data was available. For these HCPCS codes, we calculated the value of the following discounts and rebates:

340B Discount

For each of the twenty-eight HCPCS codes, we analyzed on a yearly basis the percentage of total Medicare Part B units administered in the 340B hospital setting. We then applied that 340B utilization rate to total WAC sales for the product in the year and adjusted the resulting amount downward to account for Medicaid utilization at 340B hospitals that “carve out” their Medicaid patients from 340B.3

We then estimated a per-unit, per-quarter 340B price for each HCPCS code. The 340B price is set by statute to be AMP – Medicaid URA. In each quarter, we referenced the applicable ASP from CMS’ quarterly ASP pricing files (accounting for the two-quarter lag in the data) and estimated each drug’s quarterly AMP. From this quarterly AMP, we subtracted the URA, which comprises a basic rebate and an additional rebate to arrive at an estimated 340B price.

We then developed a weighted average yearly 340B price for each HCPCS code (weighting using quarterly Medicare Part B utilization) and compared that to the weighted average yearly WAC price. The percentage difference between the two is the drug’s 340B discount off of WAC, which we then applied to the amount of WAC sales estimated to have been sold at the 340B price, as described above.

Medicaid Rebates

We relied on Medicaid State Drug Utilization data (SDUD) to calculate total units reimbursed by Medicaid annually for NDCs associated with each of the twenty-eight HCPCS codes. The rebate paid on each of these Medicaid units was calculated as the difference between the weighted average yearly 340B price and the weighted average yearly WAC price, developed as described in the previous section. We multiplied this per-unit rebate amount by total Medicaid units and adjusted the resulting amount downward to account for Medicaid utilization at 340B hospitals that “carve in” their Medicaid patients.4

Federal Supply Schedule Discounts

The WAC sales data provided by IMS was broken down by distribution channel. We isolated WAC sales through the “Federal Facilities” channel and assumed that these units were purchased at a 51 percent discount off of WAC.5

Commercial Discounts

We assumed that all units not purchased/rebated through the 340B program, the Federal Supply Schedule, or Medicaid were purchased at ASP. We relied on the ASP pricing files published by CMS to calculate a weighted average yearly ASP for each HCPCS code, which we compared to the weighted average yearly WAC for the code. We then multiplied the per-unit commercial discount off of WAC by total commercial (non-340B, non-federal, non-Medicaid) units to calculate the value of total commercial discounts.

- Vandervelde, 340B Growth and the Impact on the Oncology Marketplace, BRG and Community Oncology Alliance whitepaper (September 2015), available at: https://communityoncology.org/pdfs/BRG_COA_340B-Report_9-15.pdf

- American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, Atlanta: American Cancer Society (2017), available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/ research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

- National Cancer Institute, “Cancer Statistics” [webpage], National Institutes of Health, available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/ statistics

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group, “United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report,” Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute (2017), available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/USCSDataViz/rdPage.aspxMedPAC, March 2015 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, Chapter 3: Hospital inpatient and outpatient services, available at: http://www.medpac. gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-3-hospital-inpatient-and-outpatient-services-march-2015-report-.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Fisher et , “Differences in Health Care Use and Costs among Patients With Cancer Receiving Intravenous Chemotherapy in Physician Offices Versus in Hospital Outpatient Settings,” J Oncol Pract. 13(1) (2017), available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27845870; Hayes et al., “Cost Differential by Site of Service

- for Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy,” Am J Manag Care. 21(3) (2015), available at: http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2015/2015-vol21-n3/cost- differential-by-site-of-service-for-cancer-patients-receiving-chemotherapy; L. Gordan and M. Blazer, The Value of Community Oncology: Site of Care Cost Analysis, AmerisourceBergen whitepaper (September 2017), available at: https://communityoncology.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Site-of-Care-Cost-Analysis- White-Paper_9.25.17.pdf

- Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2014), available at: https://meps. gov/data_stats/tables_compendia_hh_interactive.jsp?_SERVICE=MEPSSocket0&_PROGRAM=MEPSPGM.TC.SAS&File=HCFY2014&Table=HCFY2014_ CNDXP_C&_Debug

- Medicare Program: Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems and Quality Reporting Programs, 82 Fed. Reg. 52356 (November 1, 2017).

- MACPAC, “Medicaid Spending for Prescription Drugs,” issue brief (January 2016), available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Medicaid- Spending-for-Prescription-Drugs.pdf; MACPAC, “Medicaid Gross Spending and Rebates for Drugs by Delivery System,” FY 2016, available at: https://www.macpac. gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-28.-Medicaid-Gross-Spending-and-Rebates-for-Drugs-by-Delivery-System-FY-2016-millions.pdf

- Younts and Vandervelde (2015).

- Government Accountability Office, Medicare Part B Drugs: Action Needed to Reduce Financial Incentives to Prescribe 340B Drugs at Participating Hospitals (June 2015), available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670676.pdf1.Includes Figures 1, 4, 5, and

- Includes Figures 1, 4, 5, and

- Includes Figures 3 and 7

- “Upon enrollment in the 340B Program, covered entities must determine whether they will use 340B drugs for their Medicaid patients (carve-in) or whether they will purchase drugs for their Medicaid patients through other mechanisms (carve-out).” See HRSA, “Duplicate Discount Prohibition” [webpage] (last updated September 2017), available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/program-requirements/medicaid-exclusion/index.html

- A 340B hospital that chooses to “carve in” will receive 340B pricing for Medicaid patients, and the state is not allowed to seek rebates from the manufacturer on these

- Joseph Levy et , A Transparent and Consistent Approach to Assess US Outpatient Drug Costs for Use in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses, Value in Health (September 8, 2017). Analysis found that Federal Supply Schedule prices for a set of brand drugs analyzed was between 48.3% and 54.2% lower than WAC.

The Oncology Drug Marketplace: Trends in Discounting and Site of Care

In 2015, Berkeley Research Group professionals published a white paper studying the impact of growth in the 340B program on the oncology marketplace.1 Our research found that 340B hospitals were playing an increasingly large role in oncology despite being a higher-cost site of care. Since then, the 340B program has grown an additional 67 percent, and the shift in site of oncology care to the hospital outpatient setting has continued.

In preparing this current white paper, we sought to understand:

- What role do 340B hospitals play in the continued shift in site of care to the hospital outpatient setting, and what financial incentives exist for 340B hospitals to expand oncology services?

- How large are statutory discounts and rebates (e.g., 340B discounts, Medicaid rebates, federal supply schedule discounts) on oncology drugs relative to discretionary price concessions, and how have they evolved?

- What role may changes in the volume of statutory discounts and rebates have played in drug pricing decisions by pharmaceutical manufacturers?

The results of our analysis confirm what other studies have shown: 340B hospitals are playing an increasingly large role in oncology. Although the unintended consequences of policy decisions and market forces that have contributed to the rapid growth in the 340B program cannot be fully understood at this point, our research resulted in a number of important findings:

- Shift in site of oncology care from the physician office to the hospital outpatient setting has continued unabated since 2008, and almost 50 percent of 2016 Medicare Part B chemotherapy drug administration claims occurred in the hospital outpatient setting—up from just 23 percent in

- 340B hospitals, which now account for 67 percent of Medicare Part B hospital oncology drug reimbursement versus 38 percent in 2008, have played an outsized role in this shift in site of

- Average profit margins on Part B-reimbursed physician-administered oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price increased from 40 percent in 2010 to 49 percent in 2015 and have created substantial financial incentives for 340B hospitals to expand oncology services, despite overall healthcare costs increasing as a result of this shift in site of

- Growth in 340B purchases of oncology drugs and the expansion of Medicaid tripled the volume of statutory discounts and rebates on drug sales between 2010 and 2015, putting upward pricing pressure on drugs accounting for these discounts and

Background

Over 15.5 million Americans with a history of cancer are alive today.2 Research shows that as the overall cancer death rate has declined, the number of cancer survivors has increased.3 Additionally, the absolute number of new cancer diagnoses has continued to rise annually as the US population grows and ages.4 Patients are treated in a broad network of physician practices, outpatient treatment centers, dedicated cancer hospitals, and inpatient facilities across the country. However, as demonstrated in Figure 1, where patients receive their cancer care has change substantially since 2008. Due to a variety of factors, almost half of all cancer patients are now treated in hospital outpatient facilities—up from just 23 percent in 2008.

FIGURE 1: PERCENT OF TOTAL CHEMOTHERAPY DRUG ADMINISTRATION CLAIMS IN THE HOSPITAL OUTPATIENT SETTING

Although limited research exists on the impact of this shift in site of care on patient outcomes and quality of care, there is substantial evidence that overall healthcare costs increase as a direct result of the shift in site of care. In its March 2015 Report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) commented that the shift in site of care from physician offices to hospital outpatient departments increases program costs and costs for beneficiaries.5 Other studies specific to oncology have found that the cost of care for cancer patients is significantly higher in the hospital outpatient setting than in the physician office setting, despite similar resource use and clinical, demographic, and geographic variables.6

As oncology treatment costs, which now exceed $87 billion, have continued to grow over the last decade,7 the shift of oncology care to a higher-cost setting has become increasingly important to Congress and the current administration. In an effort to prevent hospitals from being overpaid for items and services under the historically more generous Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (HOPPS), Congress passed a hospital site-neutrality payment provision in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 that lowered reimbursement for certain “off-campus outpatient departments.” In November 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services finalized the HOPPS final rule that reduced payment for certain physician-administered drugs purchased at a 340B price by almost 27 percent. This reduction in reimbursement is intended to better align reimbursement with the actual acquisition cost of drugs reimbursed through HOPPS and to lower drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries.8

The continued shift of oncology care to the hospital outpatient setting, combined with increased rates of cancer and rising drug prices, is setting the stage for higher overall costs of oncology care. Although Congress and the administrations have taken action in recent years, it is unclear what effect, if any, this will have on current trends. In this study, we explore the role 340B hospitals have played in the shift in site of care and evaluate the potential impact of growth in 340B and Medicaid on drug prices.

Findings

We developed our analysis using two distinct sets of oncology drugs. For analysis of the shift in site of care and 340B utilization rates, we relied on Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) claims (2008 through 2016), which include data on reimbursement for all separately payable oncology drugs. We utilized a combination of IMS wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) sales data (2010 through 2015) and publicly available pricing data to conduct financial analysis of sales, discounts, rebates, and 340B margins on a subset of the separately payable oncology drugs that accounted for 85 percent of total Medicare Part B oncology drug reimbursement in 2015. Detailed information on data relied upon in this analysis (including for the table and figures) and our methodological approach is included in the appendix.

Our study considered a broad range of related topics, including the site of oncology care, role of 340B hospitals in oncology, and impact of 340B discounts and Medicaid rebates on drug pricing. A clear narrative emerged from our analysis regarding the intersection of 340B and the site of oncology care and recent trends in drug pricing. Figure 2 depicts how high-profit margins on oncology drugs purchased at 340B prices are leading to a shift in the site of oncology care, resulting in upward pricing pressure on drugs.

FIGURE 2: IMPACT OF 340B ON ONCOLOGY

1. 340B Hospitals Have a Clear Financial Incentive to Expand Oncology Services

The 340B price is a statutory price derived by subtracting the Medicaid Unit Rebate Amount (URA) from the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). Because the 340B price is tied to the Medicaid URA, 340B prices track closely to the net Medicaid price. From 2011 to 2016, the average discount of a drug’s list price for Medicaid increased from 44 percent to 51 percent.9 Similarly, for the physician-administered oncology drugs included in this study, we estimate that the average 340B discount from WAC increased from 54 percent in 2010 to 63 percent in 2015, which effectively has kept the 340B price constant over this time period (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: TREND IN ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT, 340B PRICES, AND 340B PROFIT MARGIN

Medicare reimbursement for physician-administered drugs equals 106 percent of a drug’s average sales price (ASP). Figure 3 shows the historical trend in Medicare reimbursement and 340B prices for oncology drugs, as well as the profit margin realized by 340B hospitals on oncology drugs. Non-340B hospitals’ drug costs track closely to ASP, resulting in a 6 percent margin versus the 49 percent margin realized by 340B hospitals in 2015.

Table 1 depicts a hypothetical example of an oncology drug with a WAC of $10,000 per unit. Reimbursement for this drug is the same across 340B and non-340B hospitals. Because 340B hospitals purchase at a significantly lower price, however, they earn significantly greater profits on the same drugs than non-340B hospitals. This dynamic creates a financial incentive for 340B hospitals to administer a higher volume of oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price. This incentive has increased significantly since 2010.

2. 340B Hospitals Receive over One-Third of All Part B Oncology Drug Reimbursement

Growth in the 340B program has been well documented through various studies and data released by the Health Resources and Services Administration. Multiple factors contribute to growth in the program, including new entity enrollment, growth in contract pharmacy, and expansion of oncology services by 340B hospitals. In prior research, we explored factors that contributed to 340B hospitals’ expansion of oncology services and found that the financial incentives created through access to 340B prices is a primary driver of this expansion.10 Figure 4 shows the historical trend in oncology drug reimbursement to 340B-enrolled hospitals and the impact of expansion of oncology services at 340B hospitals.

FIGURE 4: PERCENTAGE OF PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT TO 340B AND NON-340B HOSPITALS

Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of oncology drug reimbursement to 340B hospitals has more than tripled, and 340B enrolled hospitals now receive over one-third of all Part B oncology drug reimbursement. During the same period, the percentage of oncology drug reimbursement to community oncology practices has declined from 72 percent to 49 percent, while non-340B hospitals’ reimbursement has remained largely unchanged. While 340B utilization rates vary across therapeutic categories and by method of administration, access to 340B pricing plays a substantial role in the site of care for physician-administered oncology drugs. Further, there is evidence that this trend will continue. Growth in 340B utilization rates of oncology drugs has historically been driven by two factors: enrollment of new 340B hospitals and expansion of oncology services at existing hospitals. Despite considerable attention having been paid to the number of new hospital enrollments in 340B over the last six years, the majority of growth in 340B utilization of oncology drugs between 2008 and 2016 actually stems from expansion of oncology services at 340B hospitals enrolled for the entire period (see Figure 5). With over 2,300 hospitals now enrolled in the 340B program, there is little evidence that this growth will slow in the coming years.

FIGURE 5: GROWTH IN PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG REIMBURSEMENT TO CONTINUOUSLY ENROLLED AND NEWLY ENROLLED 340B HOSPITALS

3. A Disproportionate Share of the Shift in Site of Care Is Attributable to 340B Hospitals

Although the percentage of Part B oncology drug reimbursement to 340B covered entities has clearly increased, multiple factors contribute to this growth, including enrollment of new hospitals. To study whether 340B hospitals are disproportionately driving the shift in site of care for oncology services, we analyzed the enrollments of two cohorts between 2008 and 2016: the first comprised hospitals that were continuously enrolled in 340B, and the second comprised hospitals that were not enrolled in the 340B program at any point. In 2008, each cohort had approximately 370,000 oncology claims (see Figure 6). However, by 2016, the 340B cohort accounted for over 920,000 oncology claims—38 percent greater growth than the non-340B cohort.

FIGURE 6: GROWTH IN PART B ONCOLOGY DRUG CLAIMS FOR 340B AND NON-340B HOSPITALS

Although both cohorts of hospitals are expanding oncology services, Figure 6 demonstrates that 340B hospitals are growing at a faster pace than non-340B hospitals as measured by oncology claims. This is potentially further compounded by findings from a June 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office, which found that in 2012 average per-beneficiary Part B drug spending at 340B hospitals was 140 percent higher than at non-340B hospitals.11 From our analysis, it is unclear whether non-340B hospitals are expanding oncology services as a competitive response to 340B hospitals’ actions or if other factors, such as the introduction of new oncology drugs and growth in the number of patients treated for cancer, are resulting in both cohorts of hospitals expanding oncology services.

4. Between 2010 and 2015, Statutory Discounts and Rebates Paid by Manufacturers Have Almost Tripled and Put Upward Pricing Pressure on Drugs

Drug manufacturers are required by law to pay statutory discounts and rebates for drugs purchased through various federal programs and agencies. These programs include 340B, Medicaid, and government agencies that purchase through the federal supply schedule. In 2010, the statutory discounts and rebates on the oncology drugs included in our financial analysis were approximately $1 billion and represented 7.4 percent of total gross sales for these drugs. By 2015, statutory discounts and rebates on the same set of drugs exceeded $3 billion and represented 14.4 percent of total gross sales for these drugs. It is evident from Figure 7 that the primary driver of the increase in statutory discounts and rebates is the 340B program. The growth in 340B discounts is a function of both a higher volume of oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price and a larger average 340B discount amount on these drugs, as noted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 7: CHANGE IN STATUTORY AND DISCRETIONARY PRICE CONCESSIONS ON ONCOLOGY DRUGS

As statutory discounts and rebates increase, net sales realized by drug manufacturers decline, which places upward price pressure on drugs. These pressures can lead to higher list prices or reductions in discretionary discounts and rebates to commercial purchasers, such as group purchasing organizations and community oncology practices, to offset growth in statutory discounts and rebates. Although the volume of discretionary discounts offered to commercial purchasers increased between 2010 and 2015, discretionary discounts as a percentage of gross sales actually declined from 10.1 percent to 9.4 percent.

Similarly, the growth in statutory discounts and rebates puts upward price pressure on new launch drugs. Consider a drug that is launched in 2010, when statutory discounts and rebates represented 7.4 percent of gross sales. A launch price of $100 would net $92.60 when accounting for statutory discounts and rebates. However, by 2015, the same drug would need a launch price of $108.10 to net the same $92.60 due to the increase in statutory discounts and rebates.

Additional upward price pressure for launch drugs exists because the 340B price can only increase at the rate of inflation. As a result, pharmaceutical manufacturers must account for the likely continued expansion of 340B utilization in the future to properly price a drug. Given recent growth trends in the 340B program, manufacturers are likely anticipating greater 340B utilization in the future and factoring it into launch prices.

Conclusion

Oncology is undergoing a dramatic shift in site of care from the physician office to hospital outpatient setting. Fueled by profits on oncology drugs purchased at a 340B price, 340B hospitals are expanding oncology services while at the same time increasing costs for patients and payers. Recent trends in 340B utilization indicate no slowdown of program growth in the near term. Reports by GAO, MedPAC, and others have highlighted this increased cost burden, and the current administration has taken action to offset some increased costs to Medicare patients.

This study also demonstrates how growth in statutory discounts and rebates—primarily 340B discounts—leads to upward price pressure on drugs. Absent additional legislative and/or regulatory action, we believe the trends identified in this study will not only continue but potentially accelerate in the coming years.

Appendix

The analyses in this report fall within two categories: shift in site of care/340B utilization analysis and financial/pricing analysis. Each category of analysis relied on a distinct subset of oncology drugs and different data sources. In addition to providing detail on which oncology drugs are included in our analysis and data relied upon, we also provide detail on our methodology and assumptions.

1. Shift in Site of Care/340B Utilization Rate1

The primary data source for this set of analytics was Medicare FFS claims data for calendar years 2008 to 2016. Specifically, the datasets analyzed were the following:

- Medicare Outpatient Research Identifiable Files (RIF) for 2008 to These data sets provide 100 percent of Medicare FFS claims submitted by institutional outpatient providers.

- Medicare Carrier Limited Data Sets (LDS) for 2008 to These data sets are also known as the Medicare 5 Percent Carrier Files or the Physician/Supplier Part B Claims Files. They contain a 5 percent sample of fee-for-service claims submitted on a CMS-1500 claim form, primarily by non-institutional providers.

These claims datasets include reimbursement amounts by Medicare and its beneficiaries, as well as HCPCS codes identifying specific drugs and chemotherapy administration procedures.

Shift in Site of Care

For the shift in site of care analysis summarized within Figure 1 in this report, we counted, on an annual basis, all claims within the Medicare Outpatient RIF with a bill type beginning 13 (Hospital Outpatient) or 85 (Critical Access Hospital) where a chemotherapy administration code within the CPT code range 96360 to 96549 was used and where a diagnosis code of cancer appeared on the claim. A diagnosis of cancer includes a primary or secondary ICD-9 or ICD-10 code within one of the following ranges:

We applied the same parameters (with the exception of the bill type limitation) to the Medicare Carrier LDS file and multiplied the annual count of claims by twenty to extrapolate the results yielded from the 5 percent sample of all Medicare Physician/ Supplier Part B claims.

340B Utilization Rate

For Figures 4, 5, and 6, we analyzed Medicare claims for Part B Oncology drugs. This included HCPCS codes beginning with J9, as well as a small number of other HCPCS codes beginning with J, A, or Q that are indicated for use in the treatment of cancer. We identified all claims in the Medicare Outpatient RIF file and the Medicare Carrier LDS file where one of these HCPCS codes was listed on the claim. For the Medicare Carrier LDS file, we multiplied resulting claim counts and reimbursement amounts by twenty to extrapolate the results yielded from the 5 percent sample of all Medicare Physician/Supplier Part B claims. For the Medicare Outpatient RIF file, we further limited to bill types beginning with 13 or 85. We identified claims occurring at 340B hospitals by checking that the date of service on the claim fell within a period in which the hospital was enrolled in the 340B program based on the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs Covered Entity database. Our analyses considered both payments by Medicare and beneficiary cost-sharing payments.

2. Analysis of Sales, Discounts, and 340B Margins2

In analyzing sales, discounts, and 340B margins for oncology products, we relied on WAC sales data from IMS that was available for the period from 2010 to 2015. We used this data to analyze a set of oncology drugs corresponding to twenty-eight distinct HCPCS codes/eighty-two National Drug Codes (NDCs). We selected these twenty-eight HCPCS codes following a validation review in which we compared WAC sales to available public benchmarks (i.e., total Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement for the drug) to ensure completeness of the WAC sales data. Collectively, these HCPCS codes account for the significant majority (85 percent) of total Medicare Part B oncology drug reimbursement in 2015, the most recent year for which WAC sales data was available. For these HCPCS codes, we calculated the value of the following discounts and rebates:

340B Discount

For each of the twenty-eight HCPCS codes, we analyzed on a yearly basis the percentage of total Medicare Part B units administered in the 340B hospital setting. We then applied that 340B utilization rate to total WAC sales for the product in the year and adjusted the resulting amount downward to account for Medicaid utilization at 340B hospitals that “carve out” their Medicaid patients from 340B.3

We then estimated a per-unit, per-quarter 340B price for each HCPCS code. The 340B price is set by statute to be AMP – Medicaid URA. In each quarter, we referenced the applicable ASP from CMS’ quarterly ASP pricing files (accounting for the two-quarter lag in the data) and estimated each drug’s quarterly AMP. From this quarterly AMP, we subtracted the URA, which comprises a basic rebate and an additional rebate to arrive at an estimated 340B price.

We then developed a weighted average yearly 340B price for each HCPCS code (weighting using quarterly Medicare Part B utilization) and compared that to the weighted average yearly WAC price. The percentage difference between the two is the drug’s 340B discount off of WAC, which we then applied to the amount of WAC sales estimated to have been sold at the 340B price, as described above.

Medicaid Rebates

We relied on Medicaid State Drug Utilization data (SDUD) to calculate total units reimbursed by Medicaid annually for NDCs associated with each of the twenty-eight HCPCS codes. The rebate paid on each of these Medicaid units was calculated as the difference between the weighted average yearly 340B price and the weighted average yearly WAC price, developed as described in the previous section. We multiplied this per-unit rebate amount by total Medicaid units and adjusted the resulting amount downward to account for Medicaid utilization at 340B hospitals that “carve in” their Medicaid patients.4

Federal Supply Schedule Discounts

The WAC sales data provided by IMS was broken down by distribution channel. We isolated WAC sales through the “Federal Facilities” channel and assumed that these units were purchased at a 51 percent discount off of WAC.5

Commercial Discounts

We assumed that all units not purchased/rebated through the 340B program, the Federal Supply Schedule, or Medicaid were purchased at ASP. We relied on the ASP pricing files published by CMS to calculate a weighted average yearly ASP for each HCPCS code, which we compared to the weighted average yearly WAC for the code. We then multiplied the per-unit commercial discount off of WAC by total commercial (non-340B, non-federal, non-Medicaid) units to calculate the value of total commercial discounts.

- Vandervelde, 340B Growth and the Impact on the Oncology Marketplace, BRG and Community Oncology Alliance whitepaper (September 2015), available at: https://communityoncology.org/pdfs/BRG_COA_340B-Report_9-15.pdf

- American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, Atlanta: American Cancer Society (2017), available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/ research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

- National Cancer Institute, “Cancer Statistics” [webpage], National Institutes of Health, available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/ statistics

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group, “United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report,” Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute (2017), available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/USCSDataViz/rdPage.aspxMedPAC, March 2015 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, Chapter 3: Hospital inpatient and outpatient services, available at: http://www.medpac. gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-3-hospital-inpatient-and-outpatient-services-march-2015-report-.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Fisher et , “Differences in Health Care Use and Costs among Patients With Cancer Receiving Intravenous Chemotherapy in Physician Offices Versus in Hospital Outpatient Settings,” J Oncol Pract. 13(1) (2017), available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27845870; Hayes et al., “Cost Differential by Site of Service

- for Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy,” Am J Manag Care. 21(3) (2015), available at: http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2015/2015-vol21-n3/cost- differential-by-site-of-service-for-cancer-patients-receiving-chemotherapy; L. Gordan and M. Blazer, The Value of Community Oncology: Site of Care Cost Analysis, AmerisourceBergen whitepaper (September 2017), available at: https://communityoncology.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Site-of-Care-Cost-Analysis- White-Paper_9.25.17.pdf

- Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2014), available at: https://meps. gov/data_stats/tables_compendia_hh_interactive.jsp?_SERVICE=MEPSSocket0&_PROGRAM=MEPSPGM.TC.SAS&File=HCFY2014&Table=HCFY2014_ CNDXP_C&_Debug

- Medicare Program: Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems and Quality Reporting Programs, 82 Fed. Reg. 52356 (November 1, 2017).

- MACPAC, “Medicaid Spending for Prescription Drugs,” issue brief (January 2016), available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Medicaid- Spending-for-Prescription-Drugs.pdf; MACPAC, “Medicaid Gross Spending and Rebates for Drugs by Delivery System,” FY 2016, available at: https://www.macpac. gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-28.-Medicaid-Gross-Spending-and-Rebates-for-Drugs-by-Delivery-System-FY-2016-millions.pdf

- Younts and Vandervelde (2015).

- Government Accountability Office, Medicare Part B Drugs: Action Needed to Reduce Financial Incentives to Prescribe 340B Drugs at Participating Hospitals (June 2015), available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670676.pdf1.Includes Figures 1, 4, 5, and

- Includes Figures 1, 4, 5, and

- Includes Figures 3 and 7

- “Upon enrollment in the 340B Program, covered entities must determine whether they will use 340B drugs for their Medicaid patients (carve-in) or whether they will purchase drugs for their Medicaid patients through other mechanisms (carve-out).” See HRSA, “Duplicate Discount Prohibition” [webpage] (last updated September 2017), available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/program-requirements/medicaid-exclusion/index.html

- A 340B hospital that chooses to “carve in” will receive 340B pricing for Medicaid patients, and the state is not allowed to seek rebates from the manufacturer on these

- Joseph Levy et , A Transparent and Consistent Approach to Assess US Outpatient Drug Costs for Use in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses, Value in Health (September 8, 2017). Analysis found that Federal Supply Schedule prices for a set of brand drugs analyzed was between 48.3% and 54.2% lower than WAC.